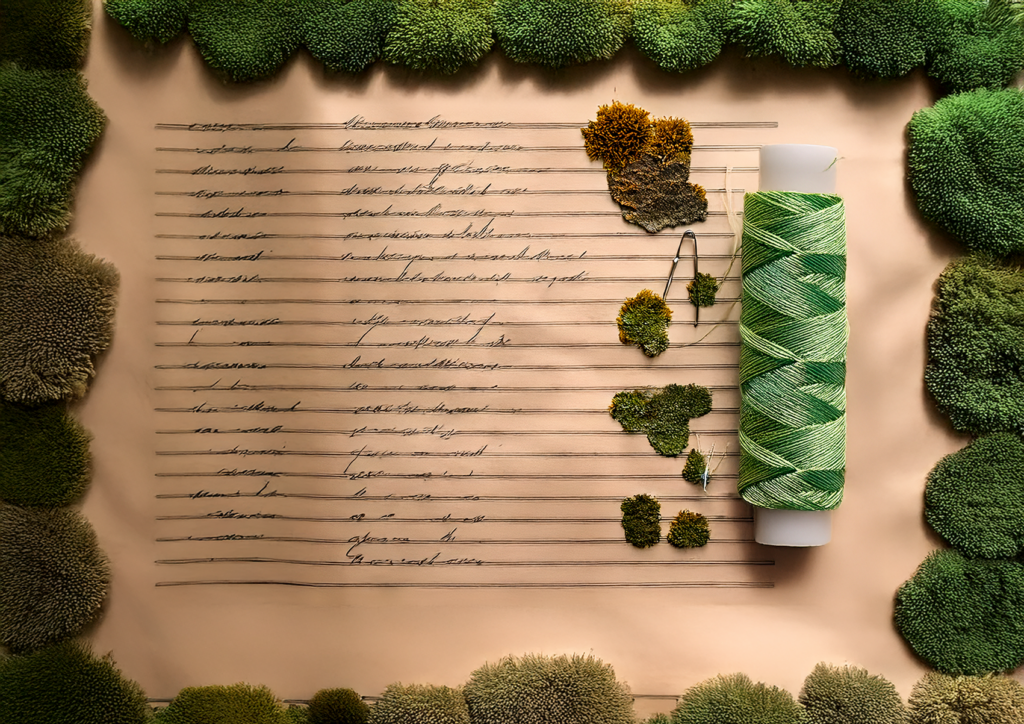

WEAVING THE WORLD: WRITING, WEAVING, AND THE THREAD OF NARRATIVES

| by Eleonora Giglione |

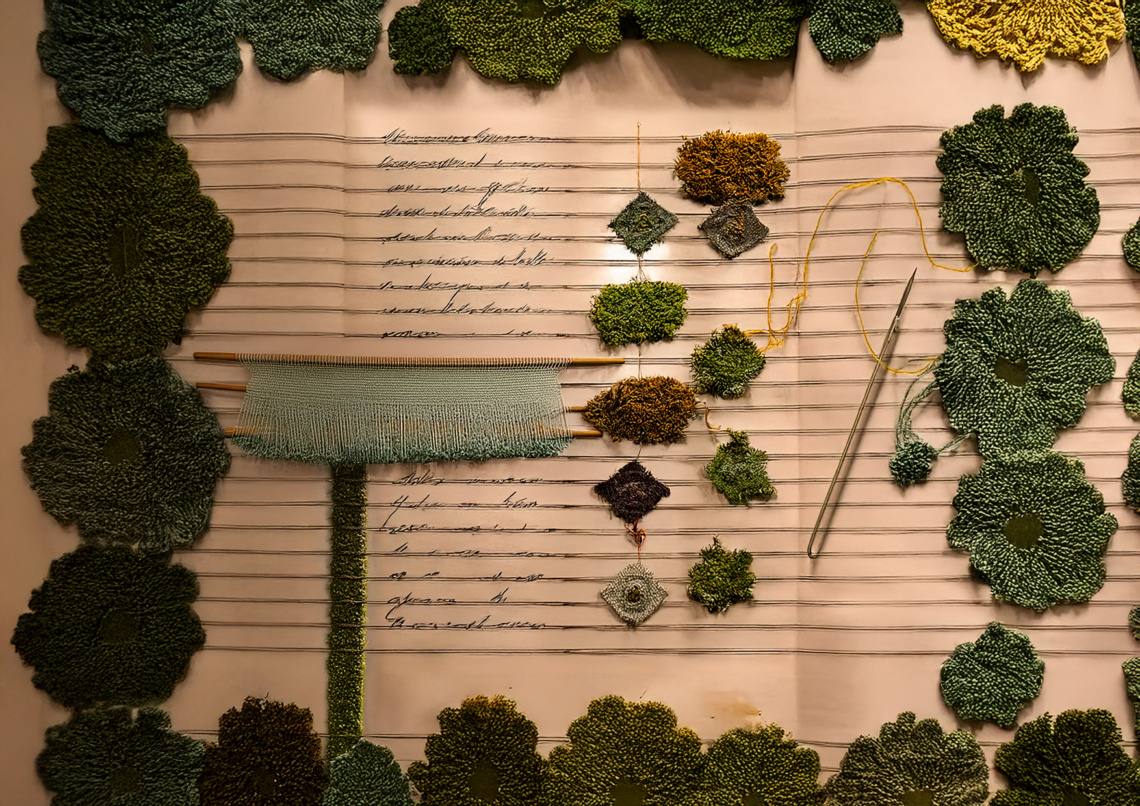

Writing and weaving have always intertwined in a symbolic dialogue: both construct complex realities by interlacing diverse elements, whether words or threads. However, the textile metaphor is not merely literary; it has deep roots in mythology, history, and philosophy. Knots, nets, and weaves not only define the structure of a text but also connect to worldviews, politics, and the art of deception. Weaving, like writing, contains an element of ambiguity and artifice. A text, much like a woven fabric, is crafted with skill, strategy, and often with the intent to conceal meanings, deceive the eye, or create illusions.

Weaving is frequently linked to the revelation of truth hidden beneath a veil. The most famous reference is undoubtedly Schopenhauer’s Veil of Maya, which obscures the true essence of reality from human sight. Penelope deceives the suitors with her weaving; the Gordian Knot is an enigma to be unraveled; Arachne challenges Minerva by weaving uncomfortable truths about the gods; Daedalus constructs a treacherous labyrinth, while Ariadne, with her thread, enables one to find the way. Like a textile, a text is upheld by the balance between order and chaos, between the illusion of form and the vertigo of the formless, guiding the reader along a thread that is both a constraint and an escape route.

The analogy between writing and weaving emerges most vividly in poetry, where verses, like the threads of a fabric, unfold in time and space with a formal rigor comparable to embroidery. Yet it is equally central to narrative, which represents the complexity of reality by intertwining different voices and perspectives. From Gadda and Manzoni to Borges, this metaphor has evolved into a structural principle: Borges explores the multiplicity of the world through plots that defy logic and linearity. In his texts, writing interlaces with textile references, both metaphorically and literally, as seen in one of his most recurrent symbols: the Borgesian labyrinth, a network of bifurcating and recombining paths, much like a narrative fabric made of overlapping warps and wefts. Borges himself, with his love for libraries and infinite textual universes, seems to suggest that every book is a thread in the fabric of knowledge, and that the reader is always a wanderer lost in the labyrinth of the text.

To navigate Borges’s vast works, one might take the short story collection The Aleph as a paradigm of his poetics. The Aleph itself, in the eponymous story, is described as the point that contains all points in space, evoking the image of a universe woven like a fabric: “[…] the place where all places on earth are, without merging, seen from every angle, (my translation)” where every point of the universe is simultaneously visible without overlap or transparency, so distinctly and clearly that it encapsulates the very essence of the universal of which it is a part: each thread is a fragment of the totality manifested within it.

Carlos Argentino Daneri, the character who guards the Aleph, aspires to write a poem encompassing the entire universe, thanks to the infinite vision it offers him. Yet his endeavor is ironically doomed to failure, for no language can truly contain everything. Borges, with his characteristic skepticism, suggests that the attempt to weave a universe into language is fated to imperfection. This recalls the ancient concept of weaving destiny, where gods or the Greek Moirai weave the lives of men, but when man attempts to replicate this process, he collides with his own inherent limitations. The idea of the Aleph as a point containing everything recalls the concept of the Persian carpet, where each knot represents a part of the cosmos. Borges, deeply fascinated by mysticism and Eastern culture, may have drawn from this symbolism to suggest that every thread of reality is connected to the others in a structure that only a few can intuit. In Oriental carpets, asymmetry is a mark of human presence within the divine work, an idea akin to the irony with which Borges illustrates Daneri’s impossible ambition. The universe is a perfect design, yet man, in seeking to imitate it, produces only imperfection.

At the end of the story, Borges reflects on the value of oblivion: forgetting the Aleph is the only way to rediscover the wonder of the world. If everything had already been seen, nothing could ever surprise us, and without surprise, thought itself could not arise, as both Plato and Aristotle asserted. Here, memory is like a fabric that unravels, a thread dissolving in time. The Aleph, like the fabric of the world, cannot be held onto. Oblivion thus becomes the process of undoing the fabric of vision, like Penelope unraveling her weaving to elude time. In this work, the threads woven by Borges stretch out to represent knowledge, destiny, and memory. The Aleph itself is an infinite tapestry, Daneri’s poem a failed fabric, and memory a thread destined to break. The universe, as in many mystical and literary traditions, is a complex and intricate fabric, where each thread is connected to the others, yet no human eye can grasp its totality.

This collection also contains more concrete references, where Borges employs weaving as a narrative element. In Emma Zunz, the protagonist works in a textile factory, and fabric becomes an integral part of her life and her revenge, the outcome of which is the result of meticulous planning, paralleling the intricate weaving of the plot itself.

In The House of Asterion, the myth of the Minotaur is reinterpreted from the perspective of Asterion himself, who recounts his solitary existence within an immense labyrinthine house. He presents himself as a being misunderstood by men, describing a world of waiting, solitary games, and an inevitable fate. This tale subverts the famous thread of Ariadne and the initiatory labyrinth of Theseus, transforming the monster into a tragic figure, imprisoned by a predetermined destiny. Here, limit and infinity become the warp and weft of the protagonist’s parable.

The Writing of the God explores writing as divine weaving: the protagonist, a prisoner, seeks to decipher a hidden text within the fur of a jaguar confined in the adjacent cell, identifying within it a secret language, a weave crafted by the divine. Absolute knowledge manifests as a fabric that unfolds, revealing its meaning only to those who can read it. Here, alluding to the ways in which divinity manifests to individuals, Borges speaks of a towering and infinite “Wheel”: “Interwoven among themselves, it was formed by all things that will be, that are, and that were, and I was one of the threads of that total weave […] (my translation)”.

Thread, fabric, and weave emerge as symbols of narration, destiny, memory, and the infinite. They are signs to be identified, deciphered, or abandoned—threads that bind us and at the same time offer an escape. Some reveal themselves in the depths of what the universe allows us to glimpse—an echo of an unreachable totality or an arabesque etched in the most unexpected places, in a finite and immutable world, or one yet to be explored.