FARIBA BOROUFAR

| by Barbara Pavan |

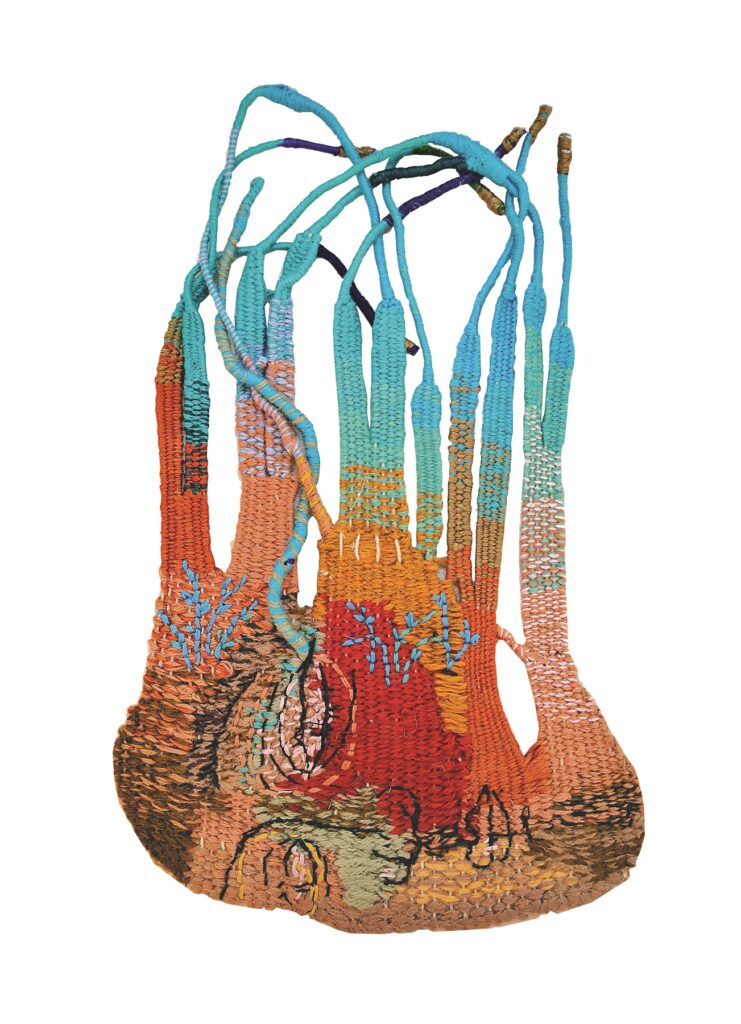

Fariba Boroufar, an artist whose works bridge the gap between tradition and modernity, uses the ancient art of weaving to explore and reinterpret the rich cultural and architectural history of Iran. Her artistic journey reflects a deep engagement with both the tangible and intangible aspects of her heritage, imbuing her textile works with a profound sense of cultural memory while addressing contemporary issues such as architectural degradation and the loss of identity. For Boroufar, being an artist means more than just the creation of objects; it is about offering new perspectives on reality. “Innovation means a new look into reality,” she explains. “The artist acts against daily life by examining the reality and changing it, forming a distinctly new world for the audience.” This process of transformation is central to her practice, where each artwork becomes a means of shifting how we perceive the world around us.

Her choice of textile as an expressive medium is no accident. For Boroufar, textiles are not only a way to craft beautiful objects, but they also serve as cultural markers that evoke memories of the past. In Iran, textiles—whether woven or sewn—hold deep symbolic significance, often passed down through generations as family heirlooms. “The textile art is the reminder of past and memories among people of Iran,” she notes. “Generally, there is a woven or sewn piece of their ancestors in their houses as a souvenir. That work shows the social, geographical, and traditional state of their era, and there is usually a story behind it.”

The inspiration for Boroufar’s work is rooted in her observations of traditional patterns, particularly those found in the needlework of Khorasan (traditional weaving Kilim in Khorasan and Yazd), a region known for its distinctive textile art. “I view the thread and fabric as flexible materials with remarkably unique expressions that result from our life culture,” she says. Her practice is deeply entwined with her studies of Iranian architecture, particularly its geometric forms. She critiques the lack of spatial awareness in contemporary architecture and the disregard for ecological materials, themes that permeate much of her work.

Boroufar’s artistic practice involves a delicate balance of theoretical study and intuitive creation. Before embarking on a new project, she immerses herself in the form and function of architectural elements, particularly those from Iran’s rich historical structures. These studies shape the themes of her work, as she explores the relationship between geometric forms and the spaces they inhabit. Her artistic process is a mixture of planned research and spontaneous experimentation. “My mind pursues the past pure forms and patterns and geometry,” she shares. “The theme flashes across my mind for a period of time until I can form a general idea.” Her work evolves through trial and error, with impromptu weavings and materials testing the limits of her concepts before they solidify into a final piece.

Boroufar’s large tapestries are a direct response to her travels through Iran’s historical buildings. “The sense of belonging to and safety in the entered places helps me to pay heed to details of all surfaces, lights, shadows, and placement of items,” she reflects. Images of textiles in the Blue Mosque of Tabriz, the stucco in the Forumad Mosque, and the painted tiles of the Seljuk Dynasty all serve as her sources of inspiration. These rich cultural and architectural symbols provide the foundation for her work, which aims to remind viewers of the histories and memories embedded within these spaces.

One of the key aspects of Boroufar’s work is her transition from two-dimensional tapestries to large-scale, three-dimensional installations. She describes this shift as a natural progression from her early experiences in sculpture and illustration. Initially, her tapestry work was rooted in surface patterns, yet over time, Boroufar began to experiment with space, light, and shadows. “I thought about how I could make a relationship between my production and architectural space,” she explains. The transition into sculpture allowed her to engage more directly with the physicality of the space in which her works were displayed. A notable example of this is her installation Penthouse, which she envisioned for the pillars of the Isfahan Jame Mosque but was initially exhibited in the less-appropriate setting of Vahdat Hall. For Boroufar, these installations are more than just aesthetic expressions; they are deeply embedded in the conversation about architectural preservation and the degradation of identity.

Some of Boroufar’s works also involve wearable elements, such as masks, which serve as a kind of second identity for the wearer. She views the relationship between the body and her work as one of transformation, where fibers become more than just materials—they become vehicles for conceptualization. “Fibers enjoy great flexibility on surfaces and can change the cover, patterns, and even function of surfaces,” she notes. In Iranian culture, the woman’s body has always been covered, and Boroufar’s exploration of body and textile intersects with this cultural backdrop.

Despite the richness and depth of her artistic practice, Boroufar faces significant challenges, particularly in terms of presenting her work in public spaces. “My most difficulty concerning this unknown medium as an independent visual work rather than handworks is presentation of my works,” she admits. The lack of opportunities to display her works in galleries and the limitations of presenting her installations in national and historical places are obstacles that she continues to navigate. Social media has become an important platform for sharing her work, but it limits the audience’s ability to fully interact with the pieces. Boroufar acknowledges that these works demand a more engaged experience, one that can only truly unfold in person.

The reactions to Boroufar’s work are varied. While some members of the audience respond enthusiastically to her exploration of textile as a medium for serious conceptual art, others—particularly those who come from traditional backgrounds—may not immediately recognize her work as independent or serious. “They traditionally look for these works and have valuable carpets and rugs in their houses,” she observes. For Boroufar, this reaction underscores the challenge of shifting perceptions about the role of textiles in contemporary art. Her work is not about creating traditional rugs or household items; rather, it is about using weaving as a tool for exploring broader themes of cultural preservation, architectural integrity, and identity. Fariba Boroufar’s artistic practice stands at the intersection of tradition and innovation. Her work is a call to recognize the value of heritage while critically engaging with the pressing issues of the present. Through her intricate textiles and large-scale installations, she not only reimagines the role of weaving in contemporary art but also creates a dialogue between past and present, space and form, tradition and transformation.

Fariba Boroufar (Tehran, 1975), a versatile artist who employs textile as a medium in her artistic practice, is a member of the Iranian Illustrators Society (IIS). Her education includes a diploma in sculpture from the Tehran School of Fine Arts, followed by a degree in Graphic Design from Al-Zahra University and a master’s degree in Illustration from the University of Art in Tehran.

Boroufar’s professional path started with illustrating books for children and young adults and working as a graphic designer for the youth weekly and magazine of Soroush Publications. Her role as an illustration expert at the Iranian Ministry of Education in 2002 was instrumental in the development of educational content. Between 2004 and 2008, she served as expert-in-charge and art director of Quds Daily in Mashhad, combining this role with teaching at Islamic Azad University starting in 2012. In 2013, she became an art director and consultant for Shahryar News. In 2014, she began a new chapter in her career, focusing on weaving and tapestries. She collaborated with Tehran Municipality’s Beautification Organization, designing and executing three-dimensional works and murals. In recent years, she has concentrated on creating textile art.

Her reflections on art have been featured in interviews and articles published in international magazines. Her works have been showcased in prestigious exhibitions, from the Toyama Poster Biennale in Japan to the Tehran Photography Expo, her solo exhibition at Saless Gallery, the PatterniTecture exhibition at Niavaran Cultural Center, as well as the Istanbul Art Fair and the Asia NOW Art Fair in Paris. Among her recent exhibitions are Inhabiting the World at Afikaris Gallery in Paris and her solo show In Our Bones at Isabelle van den Eynde Gallery in Dubai.