CHRISTELLE JEANNE LACOMBE: THE ART OF WEAVING THREADS AND WORDS

| by Barbara Pavan |

Christelle Jeanne Lacombe lives and works in Paris, where for over two decades she has combined her expertise in psychoanalysis with her artistic commitment. A graduate of the École Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Duperré in Paris, she studied art therapy with a specialization in visual arts. These intertwined disciplines feed her singular approach to art, where textile fibers become the medium for deep reflection, striving to embrace the paradoxes of psychic life.

A practicing psychoanalyst for twenty years, and by day a hospital worker for adolescents, Lacombe attentively explores artistic languages that resonate with therapeutic and human dimensions. The textile universe, with its weaves and symbolism, lies at the heart of her artistic practice.

Her works have gained international recognition through a series of significant exhibitions. These include her participation in the Fiber Arts Australian Biennale (2025–2026) and the Toronto Art Salon 2024, represented by the COA Gallery, highlighting the universal appeal of her work. In Italy, her pieces have been shown at the Museum of Textiles and Industrial Tradition in Busto Arsizio in a show titled I segreti del blu and in Perugia in the group exhibition Logos at the SCD Studio Gallery. In Montréal, her works have been exhibited by the COA Gallery and during the Plural Fair, confirming her ability to engage with diverse art scenes.

She was selected for the international exhibition celebrating the centenary of Janina Monkute-Marks at the Kédainiai Regional Art Museum in Lithuania. Her work was included in Appunti su questo tempo — the international contemporary fiber art biennial — held at MuRTAC, the Museum of Ancient and Contemporary Embroidery and Textiles in Valtopina, and at CasermArcheologica in Sansepolcro, Tuscany (2022–2023), with a catalog published by ArteMorbida. Her Italian journey also includes selection for Paratissima Talents in Turin.

Christelle Lacombe came to embroidery as a medium of artistic expression relatively late, only in the past decade. Her journey toward textile work developed gradually, influenced by various aspects of her life and profession—as an artist and as a psychotherapist for adolescents. “It was the adolescents who use textile mediation,” she explains, “that showed me the way to this form of expression.”

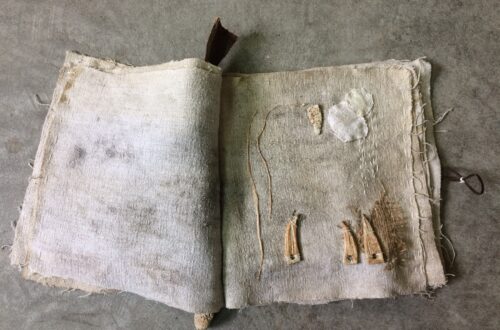

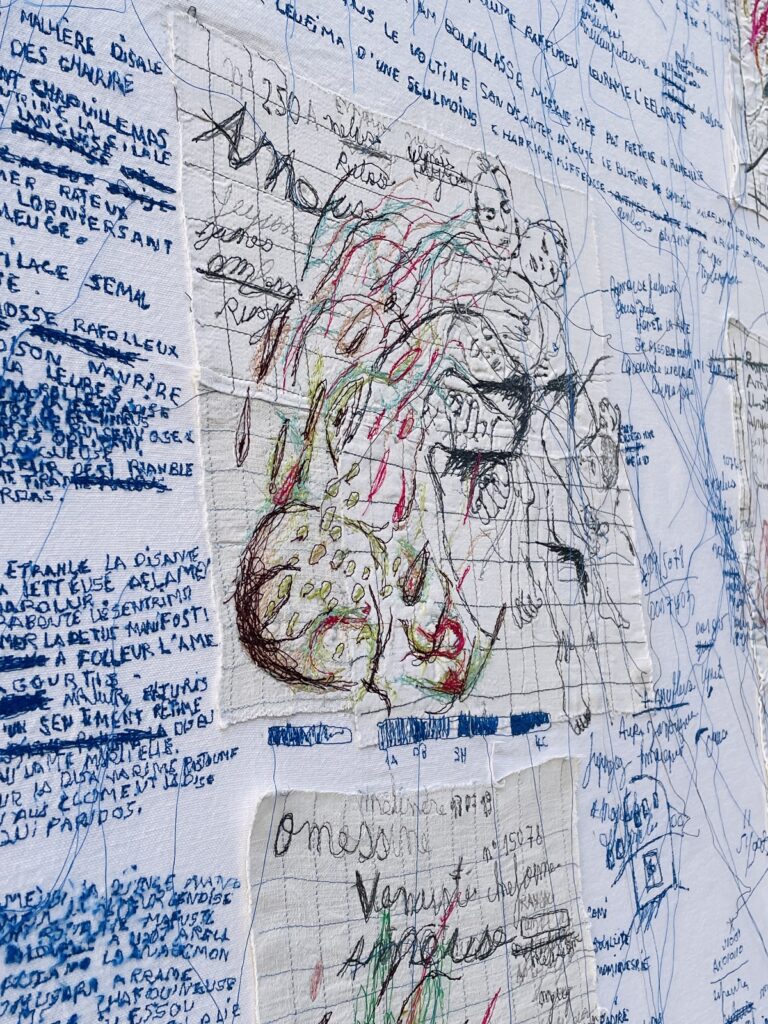

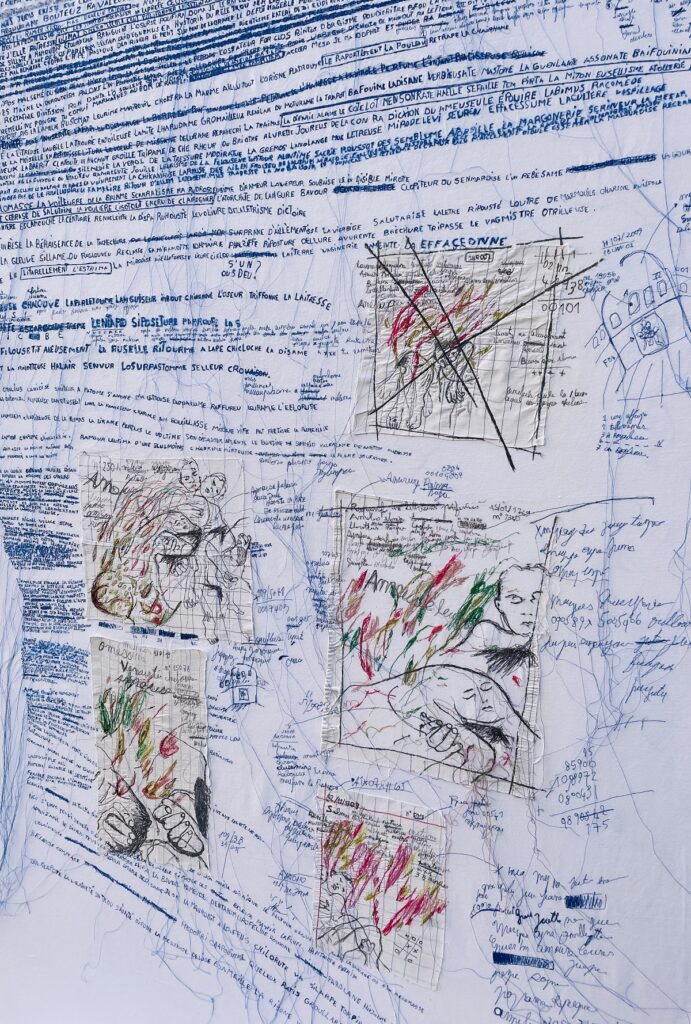

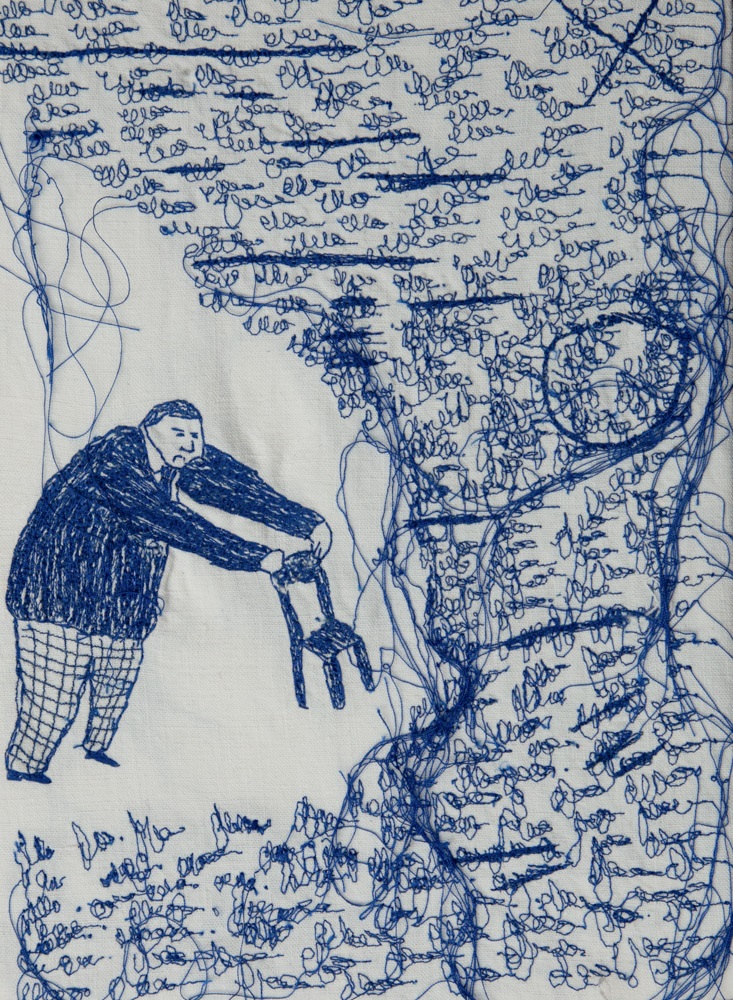

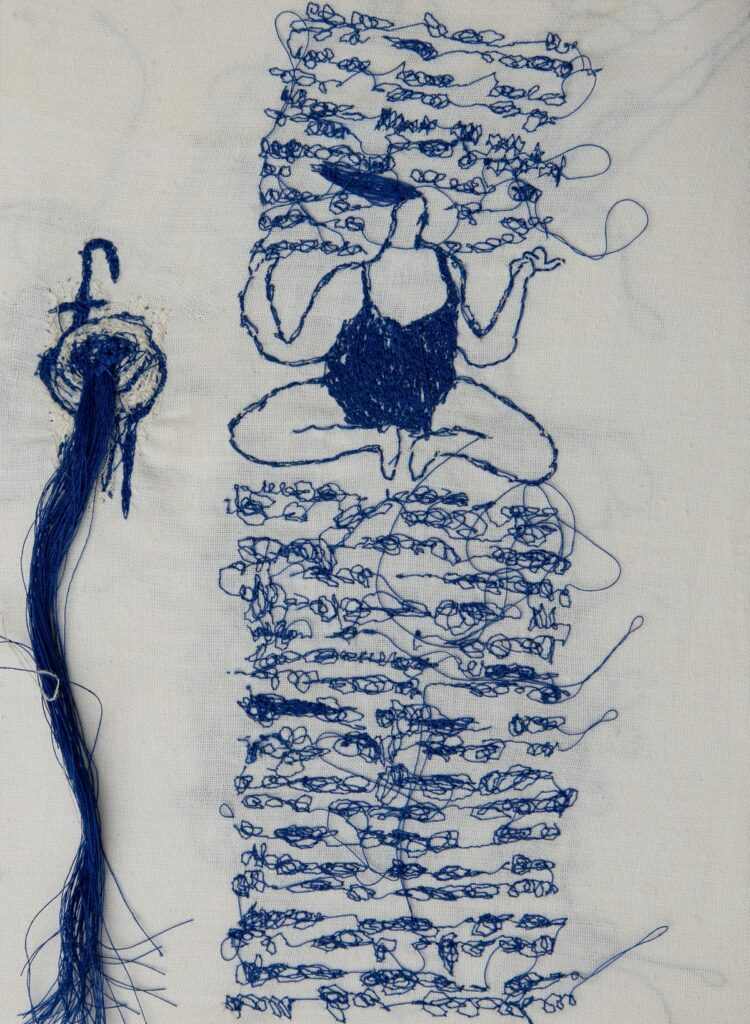

She says: “In my work with adolescents, we engage in a long process together, a kind of path marked by words and gestures. The gesture weaves, embroiders, like words that spin and wander to the slow rhythm of the work.” Thus, through sewing, assembling, and cutting fabric, a textile piece takes shape. This process represents a kind of emergence or transition, an attempt to root being in sensory experience. The textures and gestures inherent in sewing seem to create boundaries, anchoring both body and world, stitch by stitch, allowing these elements to generate small revolutions and inscribe spaces with traces left by the hand.

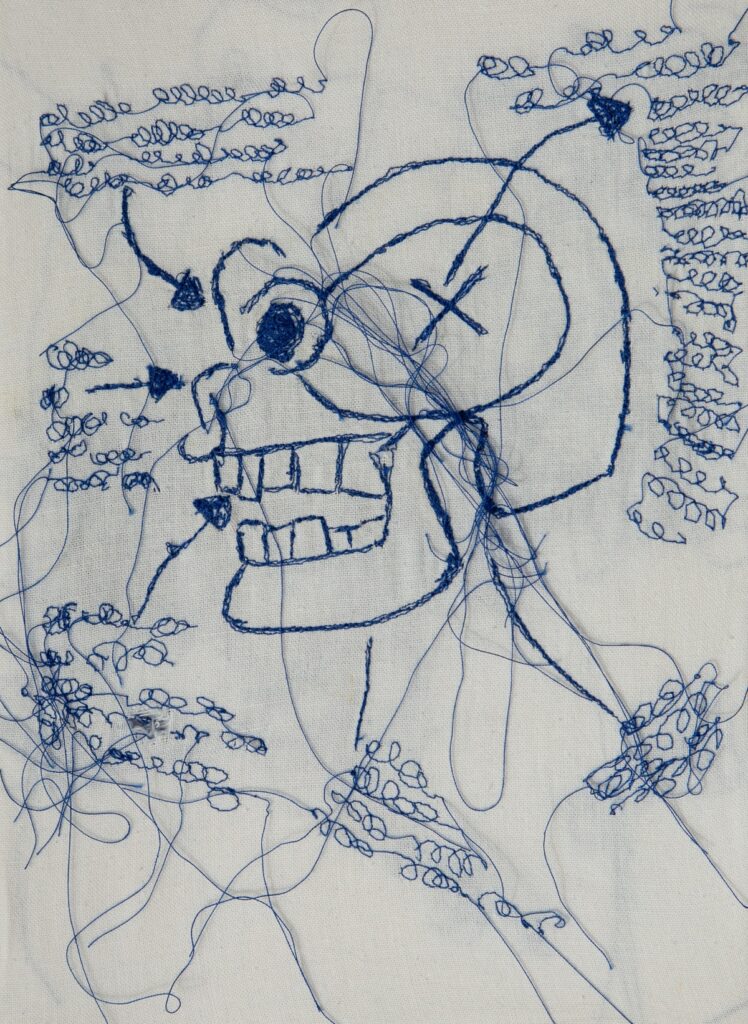

These encounters progressively oriented her creative work toward textiles, driven by a deep interest in questions linking the body to language. Her creative process draws on multiple medium: ceramics, printmaking, and textiles. Initially, she explored ceramics and textiles in a search for fictional representations of bodies, playing with the lightness and flexibility of volume. The elasticity of fabric allowed her to dissolve the conventions of figurative grammar, creating forms without figures, without ideas, without intellect.

In parallel, Lacombe also explored printmaking, where weaves, loops, and knots became like writings on copper and linoleum plates. She recalls childhood memories of knitting ritournelles with her mother, an expert in sewing and knitting, who would say, “What are you embroidering, my child… It has neither head nor tail,” while she was immersed in her craft. In this context, embroidery becomes a metaphor commonly used in popular language to denote the creation of fictions or stories. Since the Middle Ages, embroidery has been a refined technique for adorning fabrics and decorating tapestries that staged true stories.

For Lacombe, the creation of fictions through textiles is akin to what a poet does: creating space for meaning, allowing the creative act to resonate with a sense. “Fixing the thread of fiction is a necessity to provide a margin to nonsense, to steer clear of the false rigidity of meaning. It is an essential condition for the letter to carry out its work of cutting, turning, grasping, and detaching. The letter can become flesh, provided it keeps moving.”

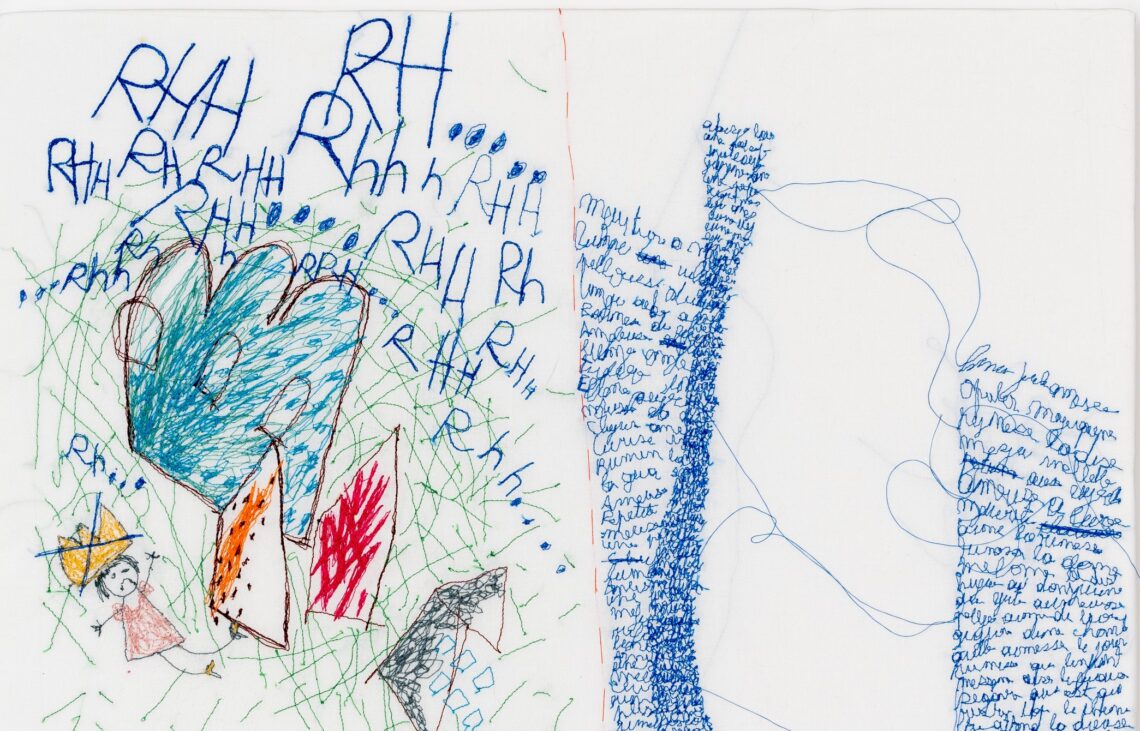

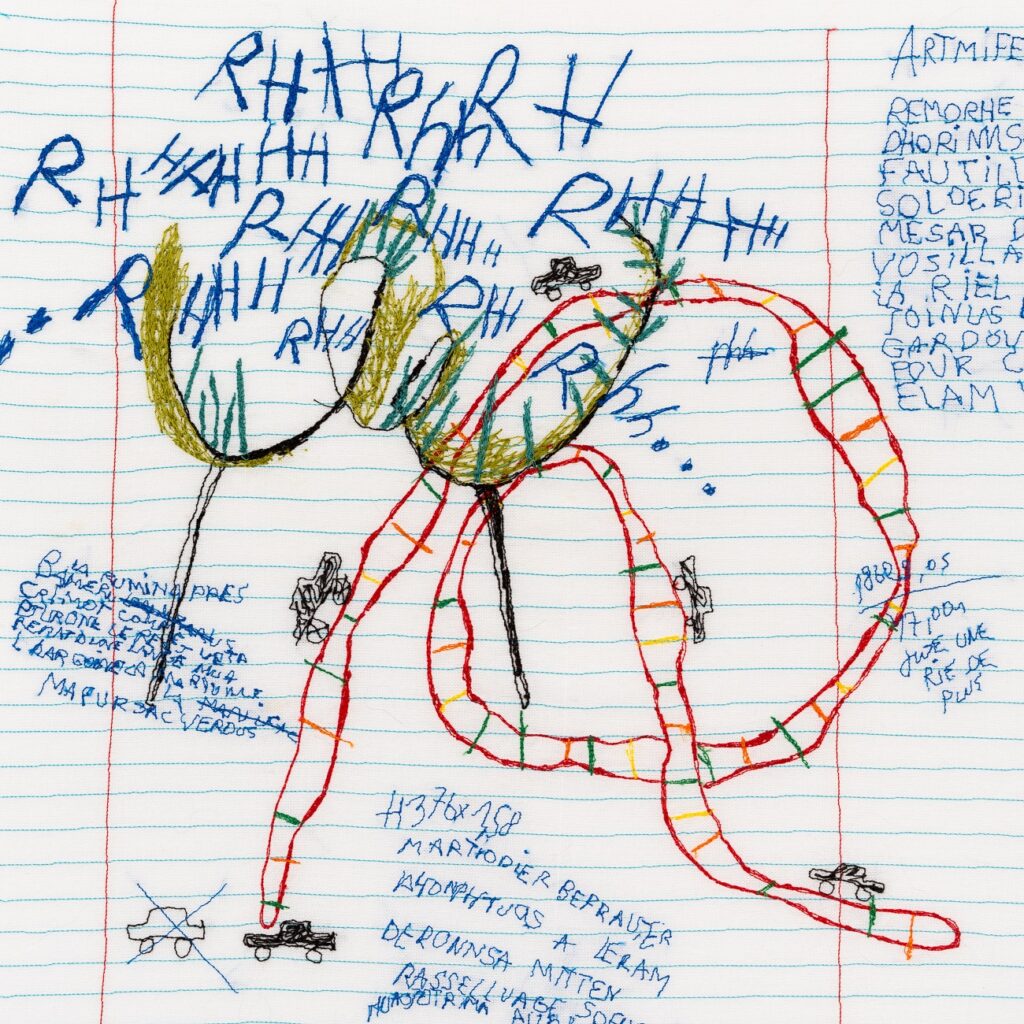

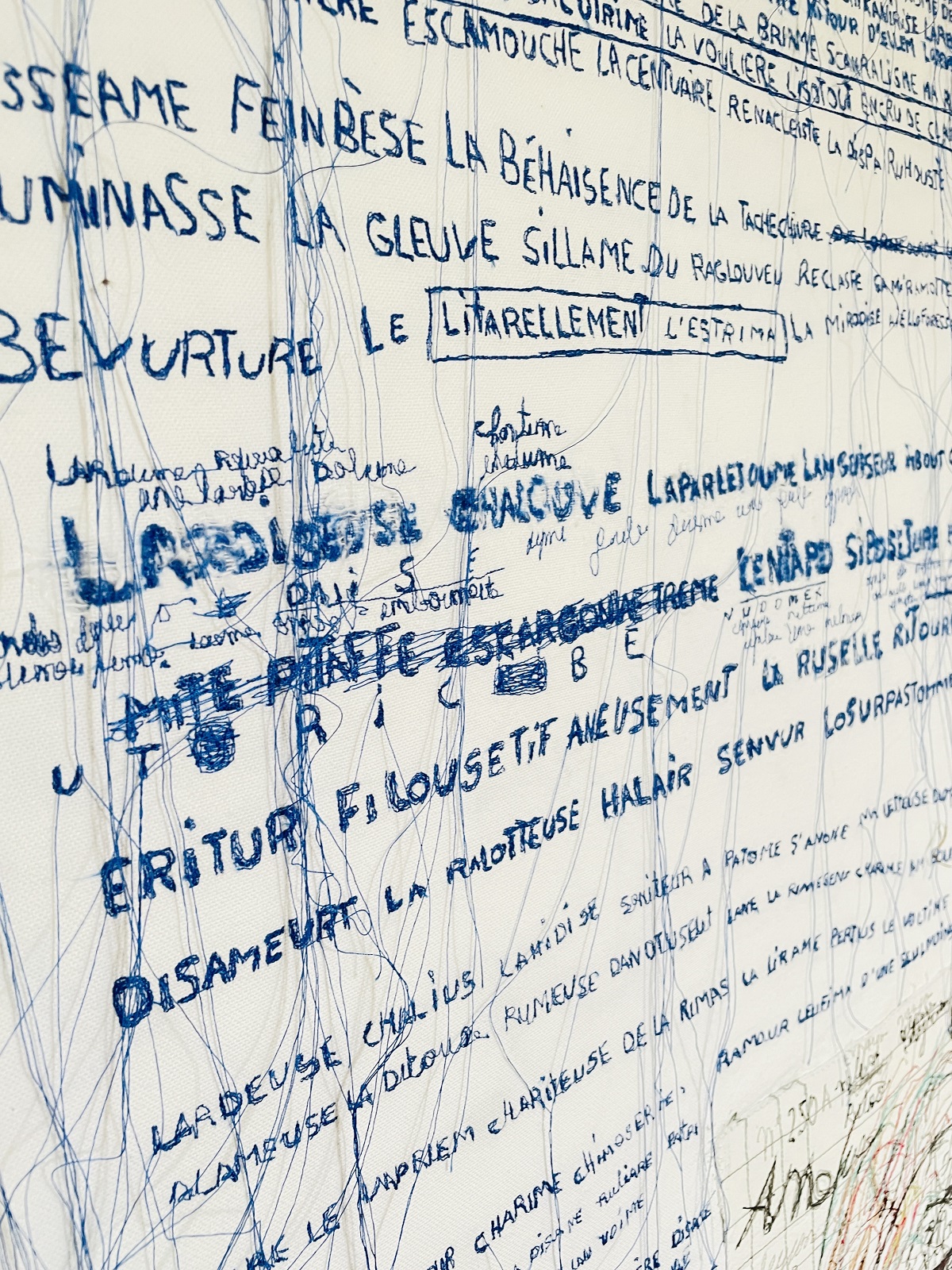

One of the most recognizable elements of Lacombe’s work is a dense pseudo-writing embroidered in blue, graphic marks that evoke a fluid, rapid cursive script with no explicit or readable meaning. Lacombe explains that being, inhabited by language, is overwhelmed by it: a bearer of words that come from within, subverting and reaching them, like words carried in veins. She adds: “The etymological roots underlying the phonological closeness of the terms ‘text’ and ‘textile’ forever bind the notion of text to the lexical field of textiles, working on the unconscious of authors like an obsession, sometimes even as a truth prematurely validated by reason.”

Lacombe references Derrida’s words, which assert that the essence of a text lies in the concealment of the arrangement, organization, and combination of the threads composing it. She continues by explaining that architecture, arrangement, and structure are concerns for shaping these fictional bodies of text—not only to escape the voracity of understanding but also to temper the excesses of the body that create barren lands. The artist likens the sewing machine to a typewriter, at times lazy, at times impatient. For her, cursive writing is a script that embraces the body—its energy, its movement, its uncertainty, its hesitation, and its urgency to inscribe an act upon a surface. Drawing from Lacan’s Encore, she notes that writing is a trace where the effects of language can be read, much like a “scribble” becomes the beginning of what one has to say. This writing, which she calls “small tongue,” sows seeds scattered across the virgin surfaces of textiles. “I take on the position of a scribe in this work, where cursive letters are a way to bring small tongue back to the surface,” Lacombe explains. Her opposition to meaning becomes, for her, a condition that allows for the creation of an imperfection within the almost perfect mechanics of the sewing machine’s rhythm. In this mechanics, she brings forth insufficiency, errors, boiling, saturation, suspension, cracks, and voids—essential conditions for language to play and create decentered spaces.

Embroidery, with its slowness, patience, and repetitiveness, approaches an almost Zen exercise. Lacombe acknowledges its therapeutic and cathartic component: “The repetitive gesture is executed under a strong impetus, from which I must let the uncontrollable emerge, while containing it. It’s a gesture that concerns me and situates me in a space.” The loose threads in her embroideries are not just a technical or aesthetic choice but also carry meaning. Lacombe sees these threads as remnants, traces of what is unfinished—a necessary condition for the work to continue. They materialize the small fall. “In Japanese, everything that leaves a trace is called time. Time and place are conjoined; the trace becomes their site.”

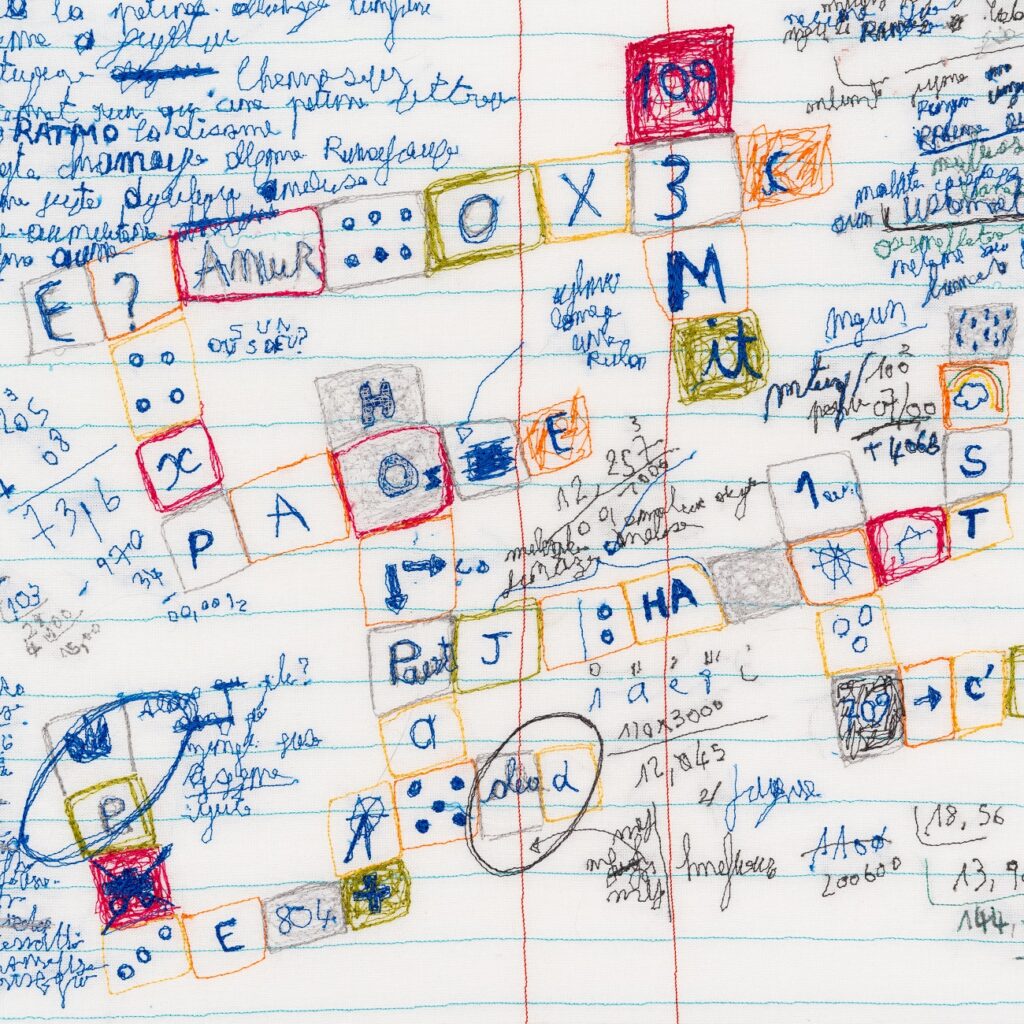

Currently, she continues her fiction-making around letters, further exploring graphic elements in colors reminiscent of childhood traces. “I embroider graphic elements close to the disturbance of childhood traces,” she says. She also develops her research on ceramic weaves, where these works respond to each other because “there are no traces carved without an initial fabric.” Her practice revolves around minimal meanings, articulated at the intersection of warp and weft, verticality and horizontality. She explains that the art of the weaver was metaphorically used in Greco-Roman myths as a tool to untangle complex matters, creating a harmonious, unified fabric worthy of clothing the great goddess of Olympus.

Lacombe works in small pockets of time, whenever possible. These intervals grant her the freedom not to overexert, ensuring that the thread continues to wander. She cites a Navajo tradition that advises moderation in weaving, even suggesting leaving the work incomplete, with an opening left somewhere. “These are the conditions that allow for differentiation and articulation between the form of the body and its background.”

Through embroidery and textile art, Christelle Lacombe weaves not only physical pieces but also complex layers of meaning, blending language, body, and material into a continuously evolving narrative.

Bibliography

Jacques Derrida, La Dissémination, Le Seuil 1972

Jacques Lacan, Encore, 1975, St-Amand, Le Seuil, p110, au sujet du texte Litteraterre et de la nuée du langage qui fait écriture. Lacan dans Encore, le 15 mai 1973 dit : « L’écriture est une trace où se lit un effet de langage. Quand vous gribouillez quelque chose, et moi aussi, je ne m’en prive certes pas, c’est avec ça que je prépare ce que j’ai à dire. Et c’est remarquable qu’il faille, de l’écriture, s’assurer.»

John Scheid, Jesper Svenbro, Le métier de Zeus, Mythe du tissage et du tissu dans le monde grec-romain, Éditions Errance