LOUISE BOURGEOIS: BETWEEN THREAD AND MEMORY, THE STORY OF AN ANCIENT CHILD

| by Eleonora Giglione |

“I am not what I am, I am what I do with my hands”, Louise Bourgeois

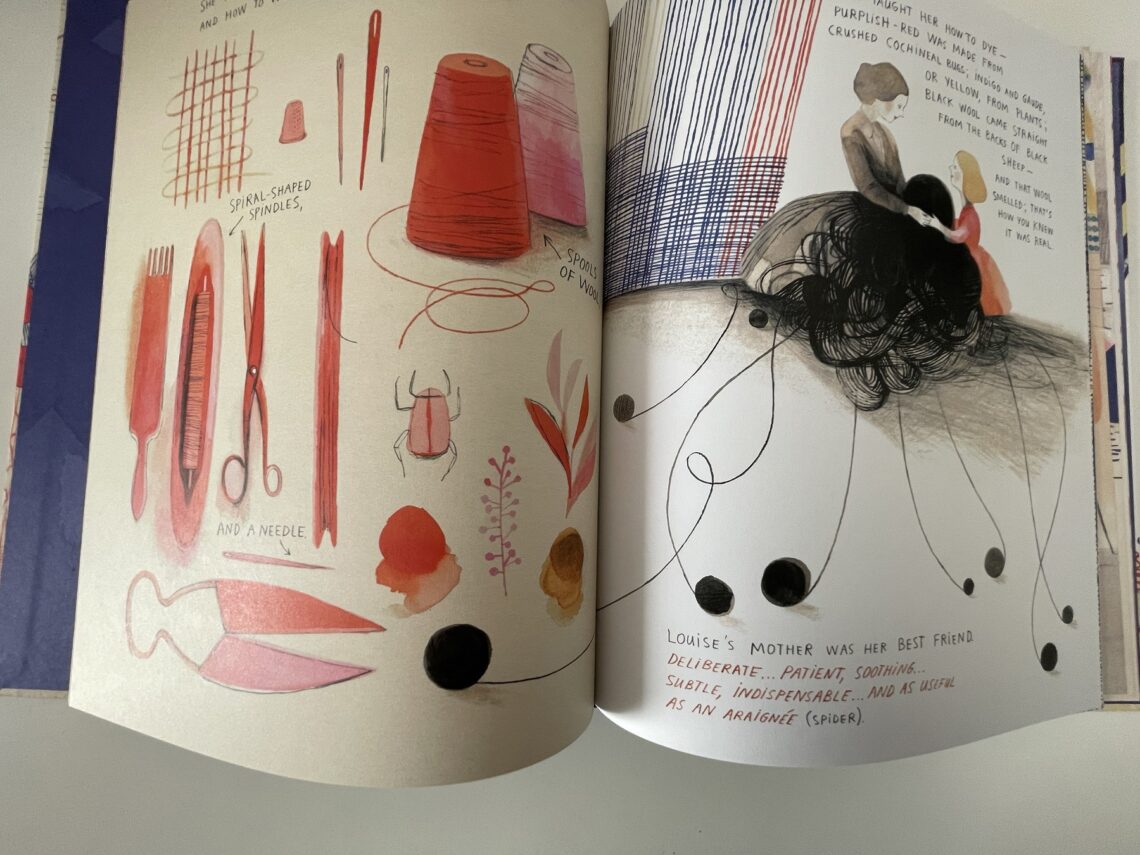

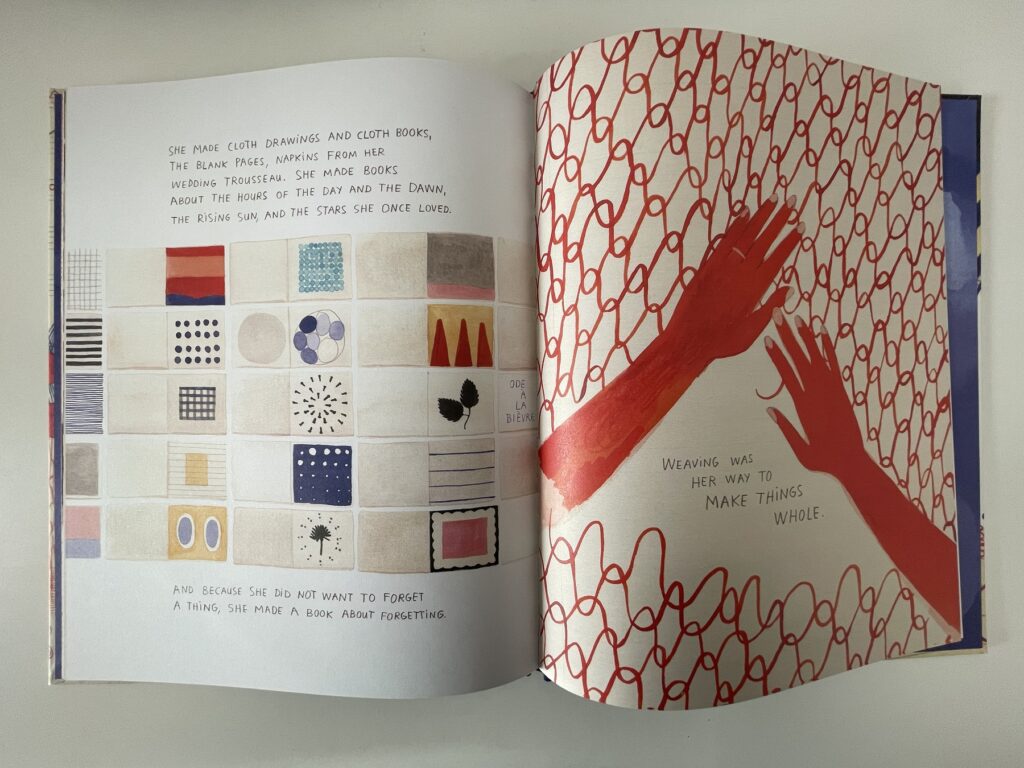

“Cloth Lullaby – The Woven Life of Louise Bourgeois” is an illustrated book for children and adults alike. And yet, both child and adult at the same time is also the soul it portrays: Louise Bourgeois, weaver of memory and matter, of threads and thoughts, of wounds and mending.

To take these pages as a starting point to narrate such a complex and intense figure carries deep meaning. Fabric and weaving are not only at the core of her art but the very rhythm of her thought: at times thin and fluid like a stream slipping between stones, at times wild and untamed like a river in full spate.

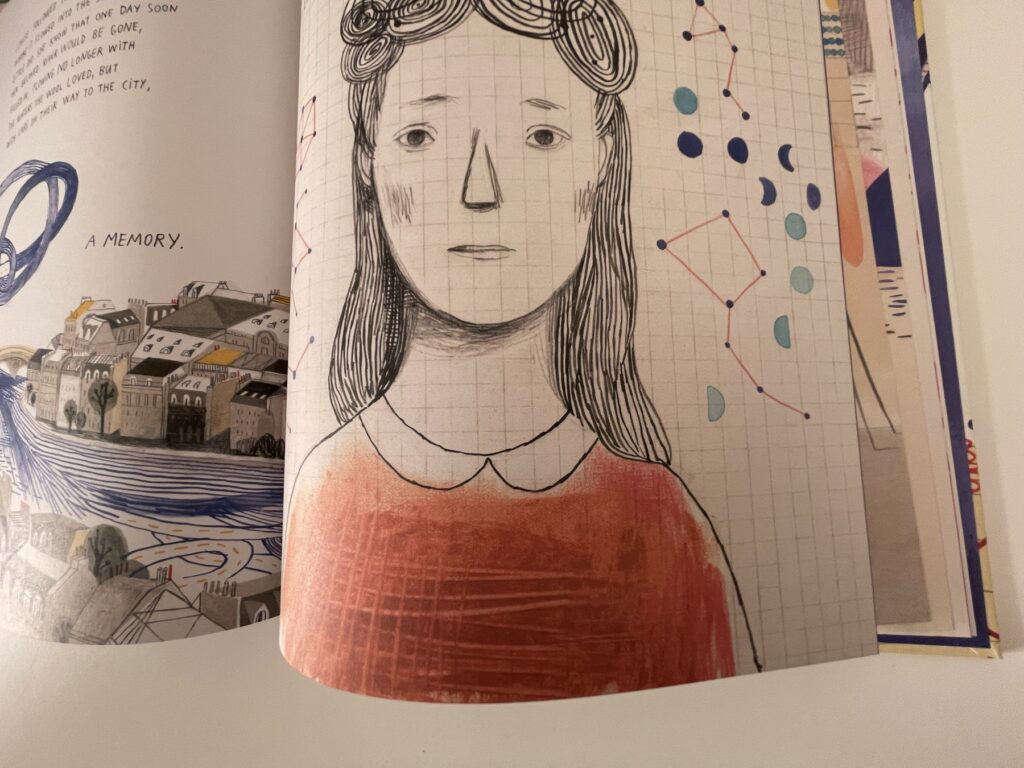

And then, the banks—the solidified thoughts, heavy as boulders, containing chaos and giving shape to the storm of emotions. And the words, relentlessly noted down, imprinted like footprints on the sand of time. Words that resurface, knots of a past that returns and intertwines with the present. Words pronounced by her parents, capable of building and destroying, of wounding and healing, of vanishing into oblivion only to reemerge, transformed, in the ceaseless flow of her creation.

A continuous epiphany, a thread that never breaks but reinvents itself in each work, over the decades, in every form her art has embraced and revealed.

Louise states that the theme always arises from the unconscious, but the form must be direct, pure, essential. The story in the book, too, begins with a river—the one flowing beside her childhood home, carving its path through her biography like a furrow in the earth. Its banks, like the edges of thought and memory, are fragile yet necessary, capable of containing the tumultuous flow of emotion.

Her artistic practice becomes, then, a delicate dam, a weave that holds and transforms, a porous boundary that gathers and returns the incandescent matter of feeling. For the body is too small for emotions so vast, too fragile to bear the weight of the invisible. So says Louise. And so, throughout her life, she tries to give form to the untamable.

Born in Paris on December 25, 1911, Louise Bourgeois slowly but progressively assumed a fundamental role in the world of contemporary art. Her career spans seven decades, with a production that intensifies and increases especially in the last thirty years of her long life, that is, from the 1980s when the artist is already over seventy. It is only in 1982 that, with a retrospective at MOMA, she gains global recognition, a fame she had never had before. Considered one of the most eminent artists of the 20th century, she has become a symbol of feminist thought, despite never having consciously placed it as the objective of her work. Louise is indeed considered an essential reference point in an artistic horizon still predominantly male. Confronted multiple times with the issue by numerous interlocutors, she reiterates that she sees herself as an artist before a feminist and that the themes addressed in her work are pre-gender, that is, elements that peculiarly belong to every human being. In this regard, she cites jealousy, the core of her production, as a feeling that does not belong exclusively to one gender but indiscriminately involves all individuals. What she emphasizes on several occasions is that artists always remain essentially children, either because they refuse to grow up or because they are incapable of doing so, thus reaffirming her focus on the way of feeling and expressing typical of childhood, purer, more direct, unfiltered: “A work of art doesn’t have to be explained, if it doesn’t touch you, I have failed.”

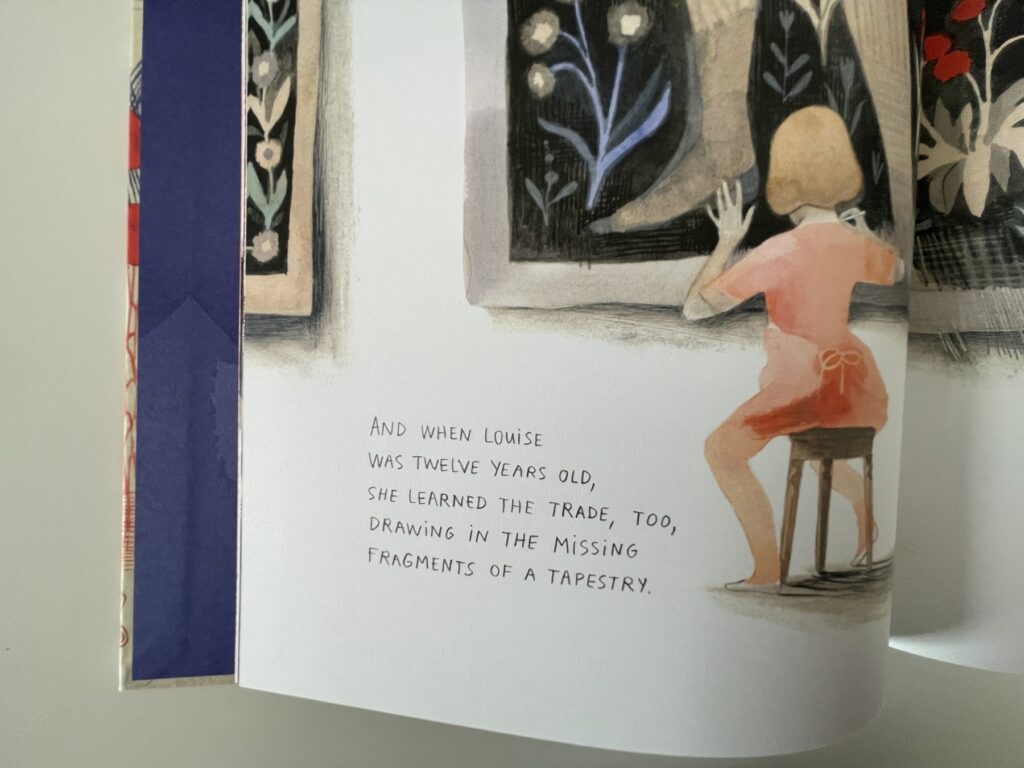

However, her life was undoubtedly directed from the start towards a valorization of freedom and individual affirmation, something that, for a girl growing up in the years between the two wars, was certainly not a given. The merit, beyond her innate determination and perseverance, is partly due to her affluent social condition but above all to her mother’s determination: “You, my daughter, will never handle a needle,” this is one of the maternal phrases that Louise recounts to us, “in her feminist attitude, my mother was virulent on that,” she continues. The family textile business indeed deals with fabric restoration, and her mother’s phrase refers to a negative connotation of loom work, as she hoped for her daughter a career of independence, which would not be limited to the humble labor of a “craft-woman.” The needle, therefore, in the feminist-inspired perspective of her mother, is seen as a symbol of the submission and servitude of women of the time. Threads and weaves, at the same time, are an integral part of maman’s daily life, a weaver by profession, and thus textile art will naturally become part of the daughter’s artistic research. Several times Louise, talking in particular about her family business and her personal interventions, will reiterate that she never actually sat at the loom.

Bourgeois first studies philosophy, then mathematics, but after her mother’s death in 1932, she abandons mathematics and begins studying art. In 1938 she moves to the United States after marrying Robert Goldwater, an art historian with whom she will have three children in the following years. After initially approaching American abstract painting, alongside friendships and encounters with figures such as Duchamp, Le Corbusier, Pollock, Rothko, her research will evolve into sculpture and installation, using different materials and techniques over time. The thematic core around which her entire production grows and expands is undoubtedly autobiographical, mainly coinciding with the dimension of childhood, accompanied essentially by parental figures, on which she alternately focuses: first on the father and, in particular, in the last 15 years of work, on the mother. Among the recurring elements, we find the house, the shape of the spiral, body parts, spiders, domestic environments, clothing, fabrics, rooms, mirrors, and relationships between people.

“My childhood has never lost its magic. It has never lost its mystery. It has never lost its drama.”

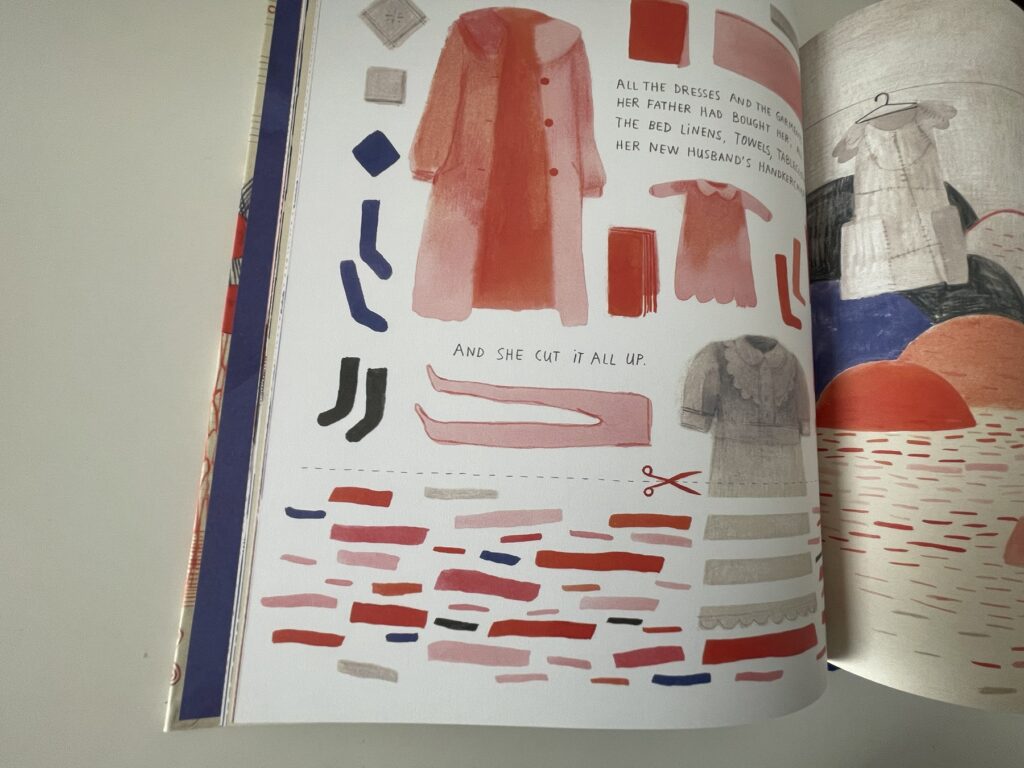

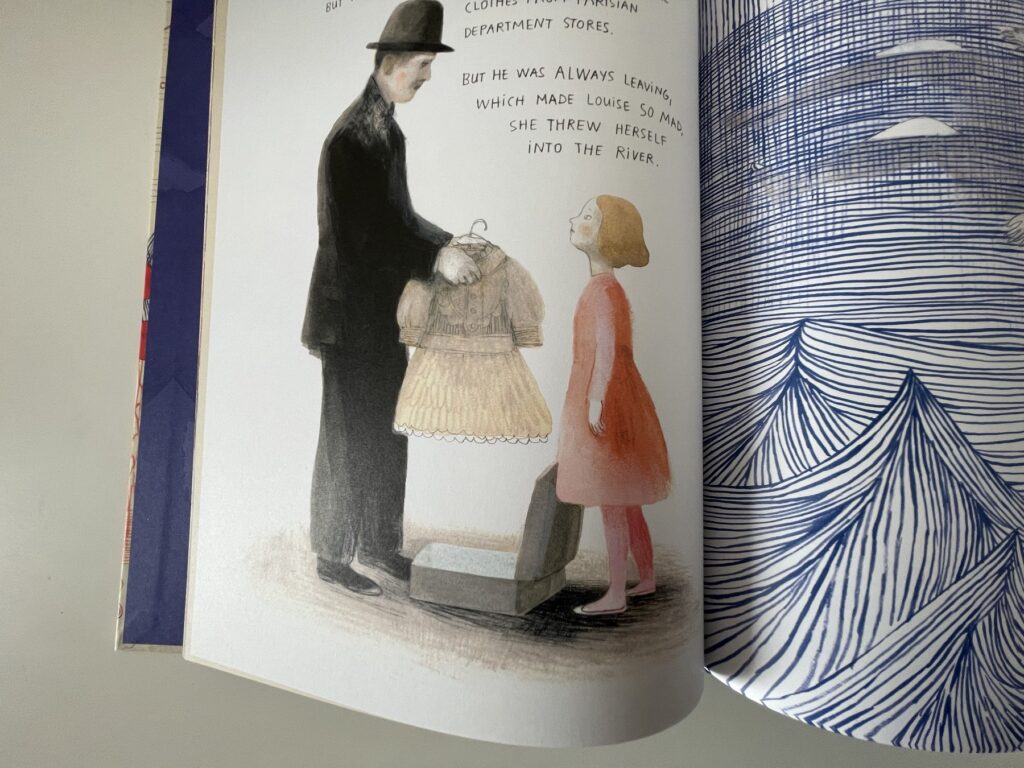

Bourgeois’s work, seen in its complex totality, indeed maintains an underlying simplicity, and probably for this reason, it has such a universally striking impact: the drama she speaks of refers to the traumatic dimension she experienced as a child due to her father’s behavior. Louise never forgave him for betraying her mother, a betrayal that lasted about ten years, with the very woman who was supposed to be her English teacher and governess, a woman who thus lived in the house, in the family, in addition to what the artist experienced as a real abandonment, when her father distanced himself from them either for work trips or to go to war. Speaking of her father’s mistress, she says: “She turned me into a wild beast.” It is as if from that moment, from the internalization of that trauma, her continuous artistic practice of “try-fail-do it again” became the only way to keep under control the overwhelming and painful emotions.

“Art is a guarantee of sanity”, Louise often repeats.

Hearing the words of Jerry Gorovoy, her long-time assistant, it becomes evident that the great control Bourgeois managed to maintain in her daily work was essentially due to the self-discipline intrinsic to artistic practice, which for the artist functioned as a true self-therapy and without which she would probably have completely succumbed to the dimension of the past, of memory, to resentment, fears, childish outbursts, pain, and jealousy, rooted in her from the earliest years of life: art is what allows her not to succumb to madness. Speaking of her father, with whom she undoubtedly had a complex relationship, Louise often mentions the fact that he would have preferred a male child. In this regard, she recalls his caustic humor, the cruel derision during family gatherings (the episode of the mandarin is famous), the fact that, if it had been up to him, she should have gotten married, been a good wife, and, literally: “Be off his hands”.

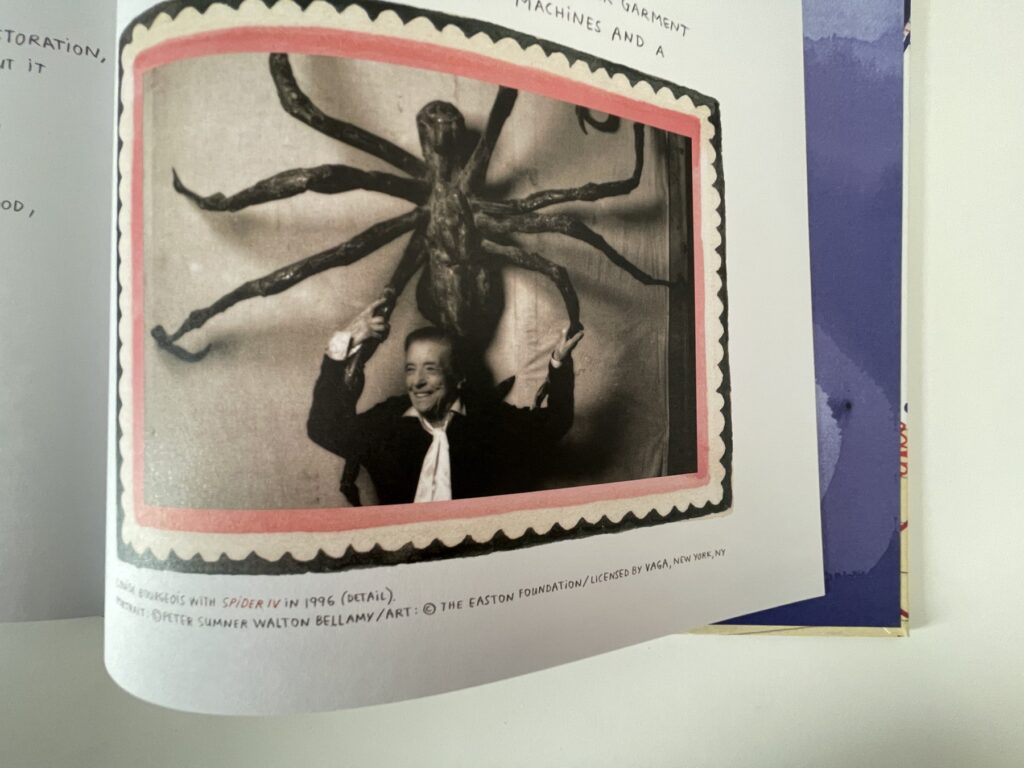

Amei Wallach, co-director and co-producer along with Marion Cajori (who passed away in 2006) of the documentary “Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress, The Tangerine” (2008), refers to the artist as an undoubtedly solitary figure, at times gruff, constantly immersed in the memories of the past, and who allows the two directors to approach her only because a substantial bond of trust is established between them. The documentary was filmed over about ten years (1993-2004), a period in which Wallach says she clearly realized that only artists and madness allow that kind of access to the unconscious dimension. She repeatedly emphasizes that what interests Louise is the creative process, not the final result. She focuses on the cathartic journey of giving shape to her works rather than on the finished object. This, in fact, constantly leads her to want to destroy parts of the works she produces, immediately after completing them, at times making it necessary for her assistant or her son to intervene to prevent her works from being irreparably damaged. In many cases, as Wallach reports, she does not even see her finished works. This is true for her monumental pieces, which she creates but never sees in their final stage. Moreover, it is emblematic that she rarely attended the openings of her own exhibitions. In her later years, Louise no longer went to her Brooklyn studio to work, so Wallach and Cajori would visit her at home to film her, often facing her refusal to be captured on camera. For this reason, many scenes in the documentary focus solely on the artist’s hands as she works.

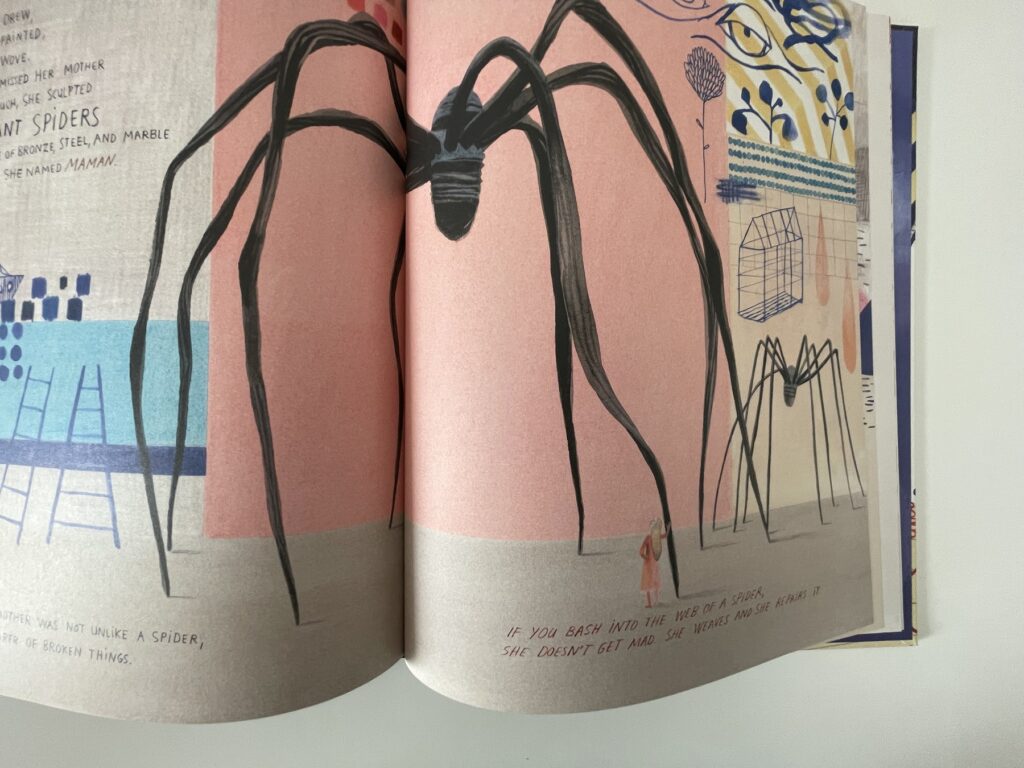

THE SPIDER

The textile idea of mending, restoring, repairing, which Louise Bourgeois retained from her mother’s activity and the family business, will evidently translate into a recurring symbolism in many works, often summarized as care, protection, self-healing. In this perspective, the figure of the spider is central, elaborated in her most popular works today. The arachnid began to be represented on paper as early as the 1940s, but it was only from the mid-1990s that Bourgeois’ sculptural production significantly focused on this subject, bringing it to the monumental dimensions recognized by much of the global audience. Despite the seemingly alien appearance of these gigantic sculptures, which look like they emerged from a dystopian science fiction film, the spider for Louise is primarily a symbol of the mother, a weaver, therefore a benevolent, protective, and patient figure. It is often depicted with a sack of eggs made of wire mesh and takes on gigantic proportions: “My emotions are inadequate to my size, my emotions are my demons”. With its legs, the spider defines a space—one that can and must be entered—a safe space. “They are intelligent and protective”, says Louise, “They kill mosquitoes”. Beyond the figure of the mother, the spider also clearly represents her artistic practice, as her assistant Jerry Gorovoy notes, because the web emerges from its body, just as sculptures emerge from Louise. The correspondence with her practice is reflected in the irregular stance of an animal in perpetual motion: in Bourgeois’ sculptural evolution, the spider’s legs are increasingly portrayed not as static but in ever more dynamic poses.

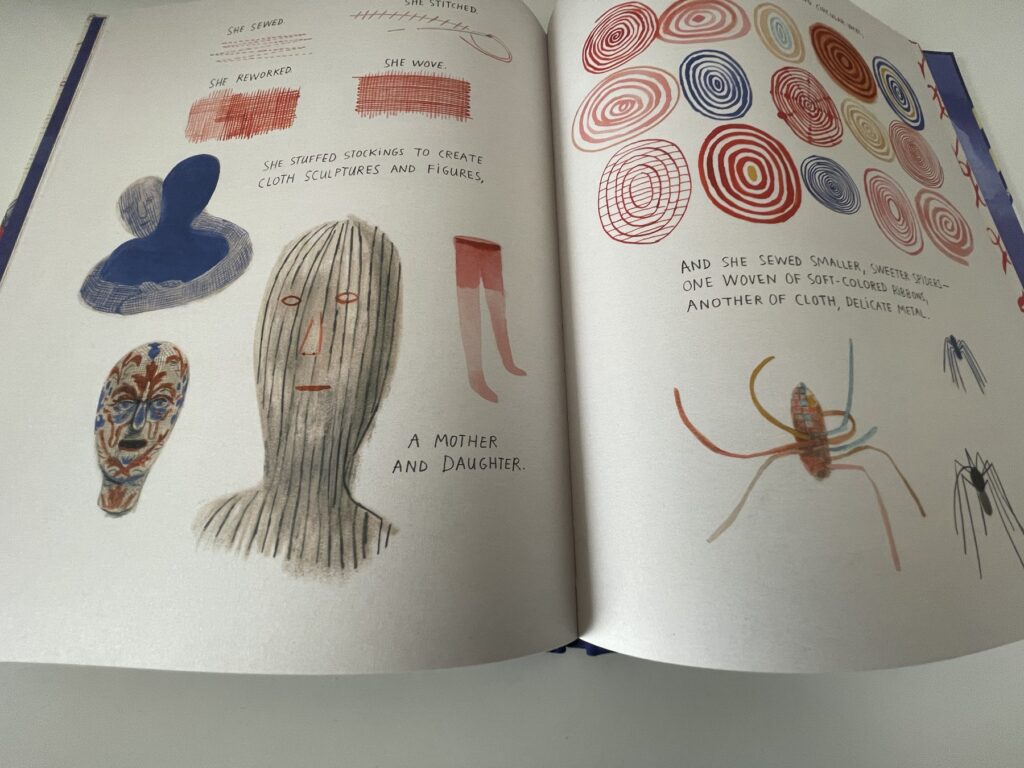

THE SPIRAL

The spiral motif recurs in many of Louise’s works, from drawings to sculptures in various materials—including textiles—and even in installations. For her, this form is a symbol of control and order, born from a twisting motion: from spools of thread and wool, certainly, but also from the act of wringing fabric—an instinctive gesture traced back to her childhood. By the river near her family’s atelier, she would wash textiles, offering her small contribution. From twisting the cloth after rinsing it, from that firm yet simple act of expelling excess water, the artist distilled the necessity of “letting things out,” of expressing. Louise also recounted dreaming that her father’s mistress suffocated in a spiral. And so, within this very symbol, we find the tragic weight of trauma, of pain, and of the resentment the young girl harbored toward her father—an anguish that indelibly marked her childhood and entire existence. For Bourgeois, a spiral is an attempt to impose order on chaos, yet it is always on the verge of slipping away, unraveling in a sudden, whirling, centrifugal motion—spiraling out of control.

THE CELLS

“The objects in the Cells are fragile. The fact that in most cases one cannot enter them has to do with the fragility of the interiors. This is a problem when they are shown to the public. I would like people to enter the Cells.”

The Cells, created in the final phase of Louise’s life, are enclosed installations, framed by furniture elements or metal bars, containing fragile objects—often made of glass, mirrors, or fabric—such as garments that belonged to her and her mother. These works recreate domestic spaces, rooms, enclosed environments that, in the artist’s vision, remain accessible, spaces where fragility is preserved. In one of her last works from The Cells series, The Last Climb (2008), Louise appears to reach a kind of reconciliation with the previously mentioned trauma. The pain embodied by the spiral form seems, in some way, to have undergone an evolution. Here, we see a spiral staircase that appears to lead outward, upward—an emergence from the confined space of the Cell. This particular installation seems to suggest ascension, perhaps an elevation, a resolution of the trauma endured.

THE MIRROR

Mirrors often inhabit the works of Louise Bourgeois, their presence recurring like silent witnesses within her Cells series. Some face outward, meeting the gaze of an observer, while others turn inward, reflecting the intimate spaces she meticulously reconstructs. The artist repeatedly emphasizes that, beyond the inherent fragility of the object itself, a mirror is not for her a symbol of vanity but rather a means of self-acceptance. She speaks of having long fled from her own reflection, of a lifetime spent avoiding her own gaze—until, with age, she finally embraces the necessity of reconciliation. To welcome one’s image, to make peace with it, is not just an act of recognition but a fundamental act of friendship with oneself.

Louise Bourgeois wrote and took notes throughout her life, during sleepless nights or vigils in which she reflected, conceptualized, and translated ideas into works. Many of these writings are now archived or sometimes partially exhibited. Some sentences have been extracted, some of fundamental importance for understanding the artist, the child, the woman Louise. One of these sentences, dating back to when Bourgeois was 47 years old, is also cited by Amei Wallach, interviewed about the 2008 documentary, and it is a rather significant statement: “I failed as a wife, as a woman, as a mother, as a housekeeper, as an artist, as a businesswoman, as a friend, as a daughter, as a sister, I did not fail as a truth seeker”.

The direct quotes are taken from interviews with Louise Bourgeois, from the documentary “Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress, The Tangerine” (Zeitgeist Films 2008), from interviews with director and critic Amei Wallach, Bourgeois’ assistant Jerry Gorovoy, and the artist’s son Jean-Louis Bourgeois. For further exploration, all materials are freely accessible on YouTube:

- A Prisoner of My Memories: Louise Bourgeois | HENI Talks

- Louise Bourgeois – ‘I Transform Hate Into Love’ | TateShots

- The Artist’s Lens: Conversation with Amei Wallach, Director of “Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress, The Tangerine” (Zeitgeist Films 2008)

- Jerry Gorovoy on ‘Spider’ by Louise Bourgeois

- Louise Bourgeois – Peels a Tangerine ZCZ Films

- Amei Wallach at Garage. Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine

- Haus der Kunst – Film of the exhibition on Louise Bourgeois. Structures of Existence: The Cells”. Haus der Kunst, 27.02 — 02.08.15

- How Louise Bourgeois Confronts the Past through Sculpture | Art21 – from the “Identity” episode in Season 1 of the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” series premiered in September 2001 on PBS.